Hinter den Regalen der unendlichen Bibliothek

Die Bücher der eigenen Bibliothek sind einer Ordnung unterworfen, die wir nicht immer benennen können. Formale Kriterien – alphabetisch nach Titel oder Nachname oder Genre – bringen Texte in eine räumliche Nähe zueinander, die beim Besuch einer unbekannten Bibliothek bedeutsam erscheinen mag. So stehen neben den Büchern, die wir suchen, diejenigen, die wir finden. Zufallsfunde, die der großen Institution ihren Ruhm verleihen und mythische Erzählungen inspirieren. Oder wir heben die Bücher als Ausdruck der eigenen Lesebiografie hervor, ihre Nähe zu uns selbst; und tun es einem Freund gleich, der seine Bücher in der Reihenfolge seiner Lektüre in die Regale stellt. Eine Bibliothek, deren nie abgeschlossene Ordnung unbegrenzt und zyklisch, deren wiederholtes Aufsuchen eine Begegnung mit uns selbst ist und den anderen eine Begegnung mit uns eröffnet. Doch sowohl in der einen wie der anderen literarischen Ordnung bleiben die Namen derer verborgen, die uns die Texte gegeben haben.

Ein solcher Herausgeber ist Hans Jürgen Balmes. Er ist kein Freund, der uns nur ein Buch in die Hand drückt. Er steht vielmehr wie Cooper in »Interstellar« hinter den Regalen der unendlichen Bibliothek, und stößt die Texte von den Regalböden herunter. Sie fallen in unsere Aufmerksamkeit. Die Momente, in denen der Herausgeber Balmes, der auch Übersetzer ist, der Lektor und Autor ist, die Tür zum Maschinenraum hinter den Regalen öffnet, sind selten. Dieser Raum ist Gegenstand dieser Textur.

Das Leben hinter den Regalen muss ein gutes sein. In einem Raum, der vor sich vervielfältigenden Dialogen brummt, in dem die Arbeit in der bescheidenen Geste des vielleicht, des oder-so vollzogen wird und im Aufrufen, Legen, Verfolgen von Assoziationen, Bildern, Referenzen besteht. Eine mental map, die Pfade aufzeigt zu Gründen, Dichtung herrlich zu finden. Darum zeigt sich uns Hans Jürgen Balmes in dieser Textur als Autor, der bald eine Naturgeschichte des Rheins veröffentlicht; als Übersetzer in einer Korrespondenz mit der Lyrikerin Nancy Campbell; als Leser in einem Gespräch mit Robert Macfarlane.

SCHREIBEN

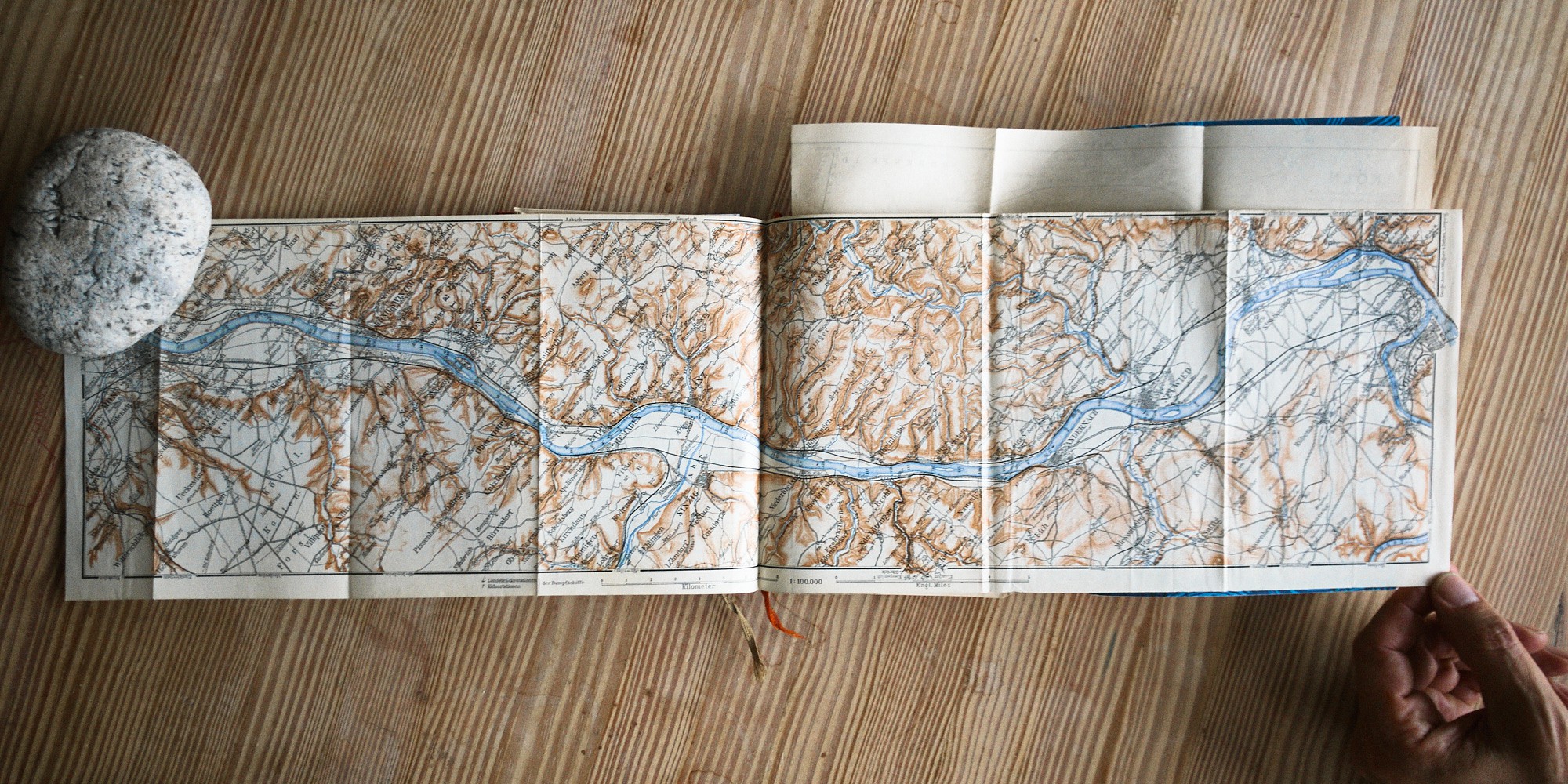

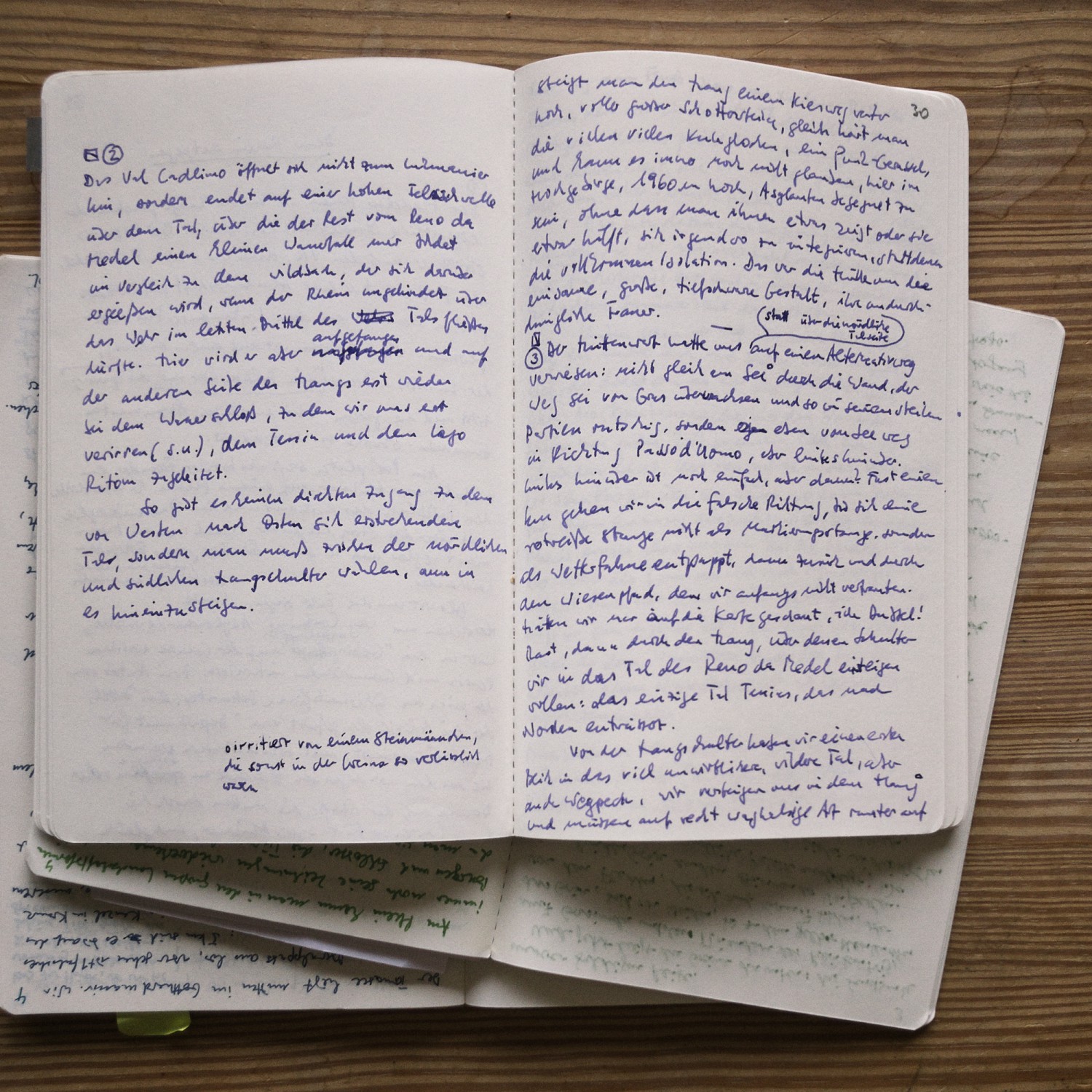

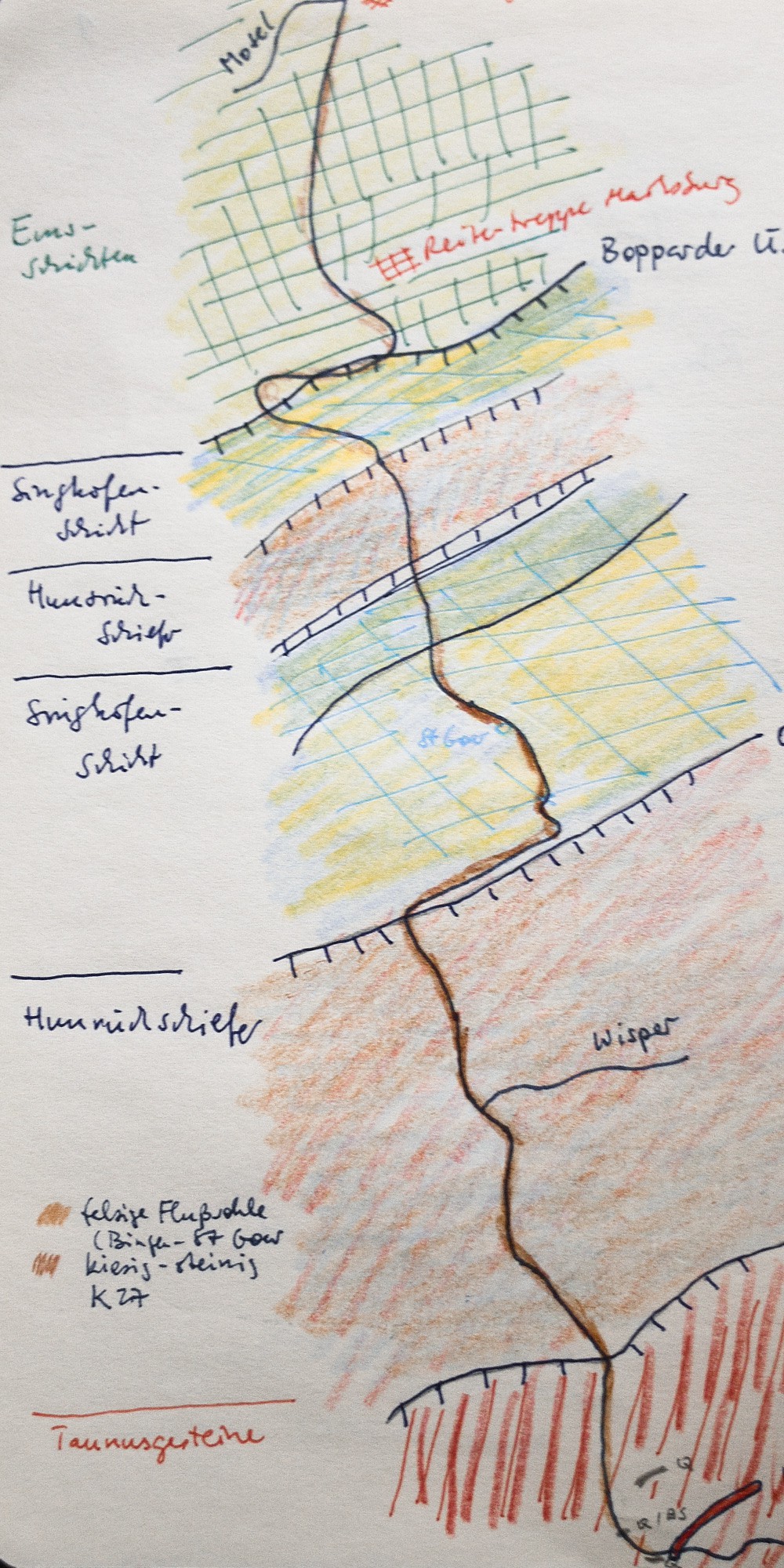

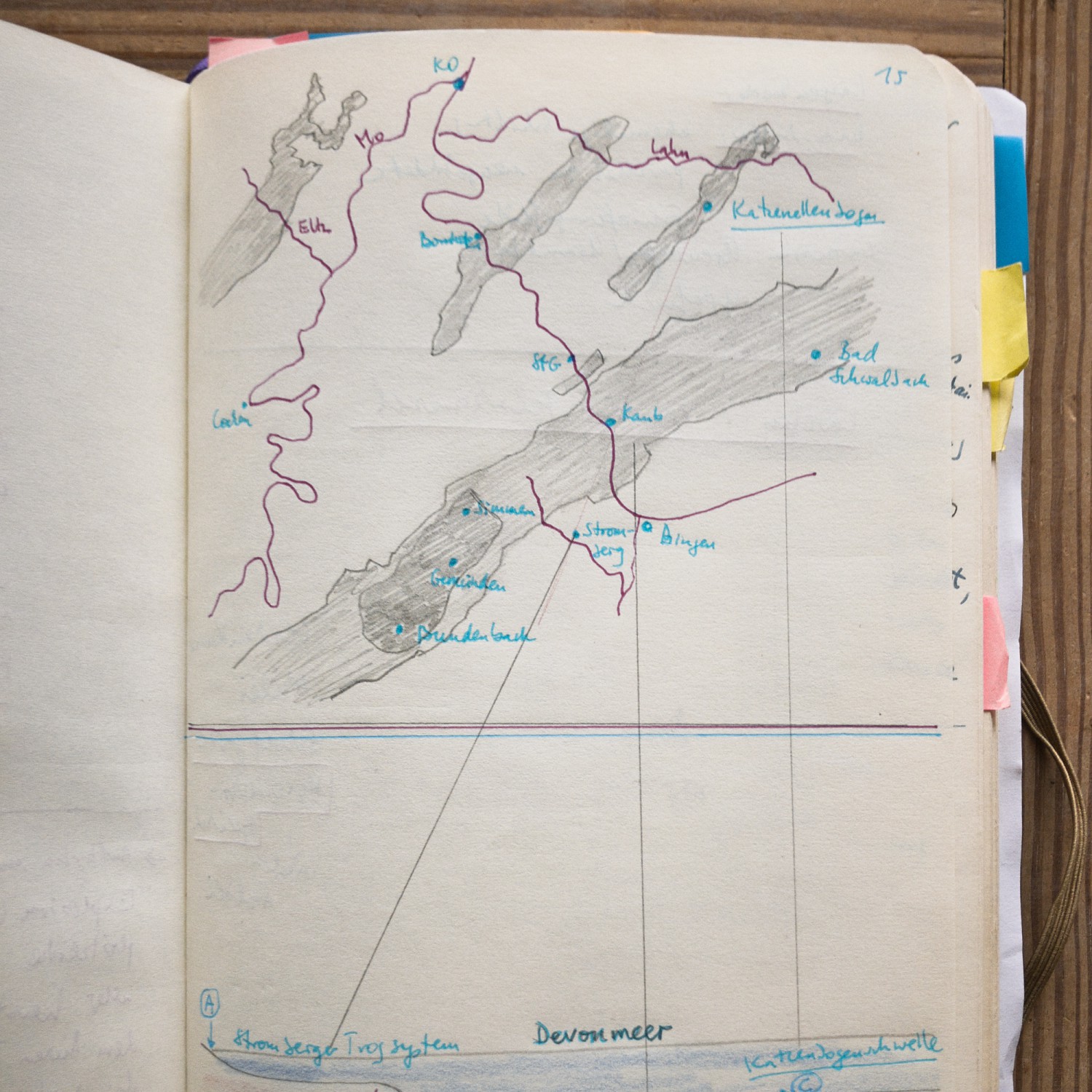

Die Vorbereitung dieser Naturgeschichte umfasst zahllose Wanderungen neben dem Fluss, im Faltboot auf dem Strom, mit dem Rhein. Es ist die Geschichte einer uns umgebenden und durchdringenden Landschaft, ihr Eindringen auf uns und unser Eingreifen in sie. So ist es auch eine Geschichte des blühenden Verfalls, die von den Rheinquellen über die Mündung hinaus bis nach London und Richmond reicht. Die in geologische und zeitliche Tiefen führt und die Dimensionen der Moleskine-Hefte sprengt, die auf allen Wanderungen stets zur Hand sind. Field notes, die die Unmöglichkeit linearen Erzählens enthalten und es so, in anderer, gedruckter Form, ermöglichen. Die das dem Fluss Abgelesene festhalten.

ÜBERSETZEN

Nancy Campbell und Hans Jürgen Balmes lernen sich in München kennen. Es gibt einen Workshop, anschließend eine Lesung. Ein Gespräch entspinnt sich, außer-analog, das sich in ihren Gedichten und seinen Übersetzungen zuträgt, das an und zwischen den Zeilen zweier Gedichte von Nancy Campbell und ihrer Übersetzung durch Hans Jürgen Balmes stattfindet. Und es beginnt damit, dass die Lyrikerin, die übersetzt wird, und der Leser, der übersetzt, Verbindungen ziehen: der sichtbare Text als Gegenstand der nachahmenden Tätigkeit der Übersetzung einerseits, die wahrgenommene Versuchung einer jäh dargebotenen Möglichkeit zu dichten andererseits. Ein Gespräch, das ist, was Übersetzung immer sein muss: die Anreicherung zweier Sprachen durcheinander.

ERRATIC STONES

Nancy Campbell

FINDLINGE

Hans Jürgen Balmes

It's strangely moving, to see the poems in a language I do not know / am so very chaotically learning – although I am like a daft spuggie [sparrow] hopping around the lines, picking up greedily on the assonances and other resonances you have created, inevitably without comprehending the depth of the work.

I sense that in these translations the poems have truly become words for readers. Generally I don't write for an audience, only to resolve a problem that the poem presents me with or – rarely – to send a private message. But the whole act of translation seems to imply communication, not just ja-ja-ja-ing alone on an iceberg. I wonder if you sense a reader when you are working or whether the process is also purely a formal challenge for you?

What a wonderful characterization of being translated! We have a lot of stuff by translators about how toilsome and heroic their practice is, always in the disguise of »theory of translation«, which I find mildly boring and sometimes infuriatingly self-important. I like Weinberger's dictum that the most wonderful thing about translating is being anonymous better. Or the Dutch novelist Bernlef, who translated Tranströmer and who said it is a great pleasure and joy to be writing poems or novels that you are incapable to write on your own.

But you are right, I maybe have an audience in mind, but also maybe only a gap between the languages, or something that does not yet exist in my language, but which I want my language to make room for. A text that should be on our shelves, too. To enlarge not only the library, but language itself. Make it richer.

I wanted to respond to this, but got caught up yesterday... just to say anonymity seems too modest a robe for the work you do, but since it is also how I aspire to write a poem, I have some sympathy. The idea reminds me of debates about the material form a book takes, the presentation of the words – as in Beatrice Warde's Crystal Goblet: or, Printing Should Be Invisible (1932). A poet’s words only move into other languages if we’re lucky, but they will almost always take material form – the work of publishing. The heroic translators even have a parallel in those who brag about making their own ink... I’ve met too many of them during years working in printshops.

I hope it doesn't diminish your work on »Ruin Island« to say that of all the texts I've ever published it's the one I'd most like to revisit and revise. I worry the sequence is full of lacunae and lacks a coherent point of view, but recently, reading Richard Price's new versions of Kiviuq and Sedna (before writing an introduction for the volume) I saw something I'd missed in my own work: how in these myths disparate sections of narrative exist and the skill of the storyteller is in building new bridges to join them – or even, blowing the fragments further apart. A formal inventiveness that, coming to the story cold, the written European tradition does not read. But these gaps are not a vacuum – through them light and sound can travel – one moment shimmering, one moment obscure – like the northern lights and full of possibility.

QUJAAVAARSSUK HEARS ADVICE FROM A MAN WHO IS NOT HIS FATHER

Listen to me, Qujaavaarssuk

sometimes others will contend with you

and sometimes they’ll tell lies

sometimes a stronger man will claim he was first to hear the whale breathing

even when he knows you heard it by night

and he did not hear it until dawn

sometimes the men in your own boat will mock you

and you’ll hear loud laughter

when all you wish to hear is your wife’s singing

and sometimes your limbs will feel heavy, the sea will launch itself on your boat

filling it with water before you can leave the shore

and while you are bailing, others will reach the hunting grounds.

Qujaavaarssuk, these things are hard, but they do not bring hunger.

Hunger will come of its own accord.

Your mail reaches deep – and I am questioning my optimistic view (there is a whole world in Ruin Island) being contested by your pessimistic view (it is full of lacunas, gaps).

Archaic storytelling is, as you have said, disparate and consists of different sections of narrative that will be held together in an oral performance. But instead of staging one, your sequence reminds one more of an old building renovated by David Chipperfield – the fragility of the old building, its damages are not repaired but exposed to signify the age, the history, and our distance to the original building, too. »The fragment is the healing part of modernity«, Thomas Kling, the late German poet said in our last interview.

So, not having a central perspective, we have shards that the reader has to put into a perspective. I have tried to follow your language and maybe stress some rhetoric (which is of course in your poem) which in German might convey some archaic tonality (like a modern version of Herder's famous collection »Stimmen und Lieder der Völker«).

Parallel sentences, sentences that point at something, not using »soft« copulas between the words, a language that is sparse but full of stresses on syllables and strong vowels (»drehten um« instead of the much weaker »wendeten«). Perhaps, if read with the right tone or cadence, this will have some incantatory quality.

Thinking about your characterization: For me, the verses are like stepping stones to cross a brook: the lacunas are there, but there are lost words, lost languages, so there must be lacunas. It is, in the end, a reconstructed culture from shards of archaeological finds.

Stepping stones call to mind the dark granite rocks at Dartmeet on the Dart – almost indistinguishable from the water – the first river I stepped across, and one for which Alice Oswald has created a new epic out of fragmentary voices. Another metaphor for the process could be found in the Qujaarvaarssuk myth, which the Ruin Island sequence retells. There was a time when ice covered the sea, leading to stagnation of the ecosystem, and starvation for people who depended on the sea for food. There was no possible movement between the worlds of sea and air for humans and animals, no »breathing holes« for the seals or »flaws« {(a wonderful term!): For cryologists, rather than the rest of us, a »flaw« is an opening that runs between ice attached to the coast (shore-fast ice) and the ice on the sea (drift ice).} for the narwhals to swim in – the region became flawless but sterile. This can occur all too easily in a text too, of course. The reader needs the stepping stones, but also the river’s flow.

I was able to gesture towards the concept of lost words in experimental bookworks, such as »Polar Tombola«, the game that you participated in at the British Council Nature Writing seminar in Nantesbuch. A game, but a poet’s serious play. How to spread an awareness of endangered languages, person by person, one word at a time? The words I chose to distribute, like qimatut (winter stores) or nunarsaq (a cavity in the ice where the seal lies) came from an old dictionary, but they had been essential to my understanding of Greenlandic culture. If, as you say, there are lacunae in each language which can host new ideas from others, it’s also true that there are lessons to be learnt the other way...

THE DAY THE TIDES FROZE

Qujaavaarssuk shuddered.

It was as cold inside as it was outside.

It was colder on land than it was on the sea.

His spit froze before it hit the ground.

The sea turned pale. It heaved and hardened

until there was not a fissure wide enough for a seal

to poke its nose through.

Qujaavaarssuk watched their shadows

moving beneath the ice.

Then they were gone

and he set out to the ice edge to follow them.

In the cycle »Disko Bay« the bilingual titles (consisting of a Greenlandic term and its English counterpart) work in this direction – two expressions in two languages, no bridge but the trust that they must mean the same. In »Lesson« you explore this distance and make it visible.

Actually in Munich, before we had really met, I was leafing through »Disko Bay« at the book stand, and these Greenlandic words caught my eye. Having translated a book about Arctic hunting and its rituals by Tom Lowenstein, I saw a connection, although he employs a different range of verse language to convey and translate his experience.

But there, and maybe even more in your book, these Greenlandic words seemed to be »Findlinge«, »found ones«, as we call the erratic stones left by glaciers. Oftentimes, they have been transported far away from their origin and lay in foreign soil. These Greenlandic words have also lost their immediate context – because the speaker with whom you speak is not so well versed in that language anymore, or the language is nearly forgotten and only some words survived because of their precision – as long as this precision is needed in a living context: hunting, observing the ice, remembering ancestors.

When we read these Greenlandic words we are like archeologists searching for entrances into a foreign context. Without commentary, we are lost in dialects, grammar. Words are like tools that we have to ask for their precise usage.

This can maybe also excuse the practice of »detour-translations«. Only very few specialists can translate these sentences and myths from the originals, so we have to take a detour through an interpreter – Greenlandic, English, German – so there is one more stepping stone needed to reach the »Findling«.

UMIARISSAAT / THE SEAL PEOPLE

I watch four shadows pass the sun.

They are not men, those bearded ones

with fat, stooped heads and shining skin

aboard a boat with no beginning.

What brings such beasts? I do not know

their stooping forms; their short, fat arms that row

the endless boat; their long, white claws;

their round, black eyes that look to shore.

They row so close I see still more.

The round, black eyes that look to shore

have seen me watch. They are not men.

The boat will disappear again.

Yes, the traveller has to be willing to make a detour sometimes. But I had the opposite sense, reading your first translation »Umiarissaat | The Seal People«, now »Die Robbenleute«. It was that quality that John Berger describes as »the third point of the triangle« or »what lay behind the words of the original text before it was written«. In this case it was as if the seals had sailed straight to Germany on their boat of ice, not passing through landlocked Oxford – you had seen the essence of the poem.

In reference to poems by the Kashmiri mystic Lal Dêd you once mentioned the »different kind of weight« of poetical images in her poems. I often experience this shift (which might have created the notion of »essence«) with poems from ancient time or from other literatures which have no common tradition with ours: Lal Dêd, Inuit, or even the fragments of Sappho in Anne Carson’s translation. Maybe this notion of a different weight is connected to the distances that these poems, fragments, images have traveled. On their way they have lost all their frames, all the soil that clung to them, they are free of context and such they can connect directly with us: there is no insulation there.

I pestled my heart in love’s mortar,

roasted it and ate it up.

I kept my cool but you bet I wasn’t sure

whether I’d live or die.

(Lal Dêd, translated by Ranjit Hoskote)

I often think of this when I read Sappho. From fragment 24D there is only left »in a thin voice«, which is the fifth line of six, all of which cannot be deciphered except »in a thin voice«. Or fragment 12 which had nine verses, only readable verse 4–5: »thought / barefoot«. Or fragment 29A: »deep sound«.

It seems to me as if these fragments are reaching out to us, they touch us with a kind of immediacy that is without parallel. Are these images and metaphors so immensely relatable because their origin is so distant?

But perhaps as with Sappho, it is the tenderness of these verses, the frailty of the few images that made them survive and cut through the distance. This is what touches me – and maybe this difficult transport which ends in a surprising emotion touches the »essence«.

I think I translate because I am yearning for this room, for this touch. As the experience in these poems is so unique I want my language to travel there. In this sense, you are right to remind me of Elizabeth Bishop’s »Questions of Travel«.

Is it lack of imagination that makes us cometo imagined places, not just stay at home?Or could Pascal have been not entirely rightabout just sitting quietly in one's room?

It is this lack that makes me travel there, but I am – contrary to you – a cautious traveler and stay in my room, like Pascal. I have crossed the Arctic Circle, but only in Norway which is very different from the experience that you make crossing the circle in Canada and, of course, in Greenland, where there is less infrastructure.

Bishop offers the reader two options: desire to travel vs stasis and study. My own travels don’t fit either of these categories. You imply I am a bold traveller – but when I reach my destination, I tend to stay in my room. And not because I’ve been overcome by rar in the Arctic winter. I venture out in minimal ways: to other people's homes, the market, to study in a new library. I like looking out of windows, I like observing the incremental changes that affect the immediate landscape over time, or learning how the language works. I like the long nights and weather conditions which give me an excuse to avoid further exploration. I've found excursions across glaciers and up mountains less rich than discovering the monotonous rhythms of daily life in a new place – not that I don’t love such hikes, but it is from familiarity, even ennui, that poems emerge.

Arctic nights are good for reading. My conversations with the Upernavik islanders were consolidated by obscure archaeological studies – gleaning fragments of knowledge that fed into the poems, such as how hunters judge the air temperature from the behaviour of a gobbet of spit.

o this was how I approached the commission from the museum to respond to the island, a place unknown to me. The language and its traces became a way in to the island's story. This is the fraught introduction that »The Lesson« describes. I did not expect one winter to become an experience I carried through another decade, and several different projects... but the material was closer than I thought to my own concerns, and would not let me go.

The presence of the Arctic in the Western imagination has changed over the last decade. It is no longer silent, a white noise on the world’s media. It’s four years since my last residency in Greenland and now I also travel back there only through books.

There’s an old story – I forget where I read it – from a time when there was more uncertainty than now about the physical shape of the Earth and what a long voyage might entail. A mariner dropped his knife overboard – it fell into the sea and he thought it was gone forever. Many years later he arrived back home to find it stuck in his kitchen table. He realised he must have been sailing directly over his house as the knife slipped from his fingers – what a coincidence! This uncanny layering of place, rather than linear distance suggests how we might inhabit multiple spaces simultaneously.

(…)

Nancy Campbell wächst in Schottland und Northumberland auf. Sie schreibt Lyrik und Essays und rezensiert bildende Kunst. Nach einer Ausbildung in traditioneller Buchhandwerkskunst arbeitet sie in Kunstbuchdruckereien in den Vereinigten Staaten und in Großbritannien. Aus mehreren Aufenthalten in arktischen Forschungseinrichtungen zwischen 2010 und 2017 entstehen vielfältige künstlerische und literarische Projekte. Für ihr Lyrikdebüt, Disko Bay, wird sie unter anderem für den Forward Prize for Best First Collection nominiert. Seit Januar 2018 arbeitet sie als Canal Laureate in Großbritannien mit dem Canal & River Trust und der Poetry Society.

I travelled to Greenland ten years ago, and then it was impossible to find any resources for learning the language in advance. I had a little Danish; English was not commonly spoken. Communication was challenging, and sign was used frequently. I realized when I reached Upernavik, one of the northernmost settlements, that written texts were regarded with some suspicion. (A legacy of an oral culture and/or resistance to an administration (Danish) perceived as foreign?) This threw my whole enterprise as writer (in English) there into some doubt. A role that had been endorsed by the (distant) government administration was not supported by the team on the ground. My learning of Greenlandic was my attempt to bridge the gap in all our expectations.

I find learning languages without seeing words written down difficult, but mostly this was how I had to manage. I picked vocabulary up piecemeal – rather than a structured system – from individuals. I had recourse to an old dictionary, which became crucial to my work, but the orthography had changed enormously since its printing in the 1930s. In the end I cannot be said to have »mastered« the language at all. But lack of mastery taught me much.

Greenlandic is an Eskimo-Aleut language. It is more densely woven than English, with its smaller alphabet (18 letters) and polysynthetic words. When it is spoken, the suffixes are uttered so softly that an untrained ear cannot hear them. Sentences seemed to trail off into silence. I began to find English finicky and prim in contrast. Greenlandic was the whole whale, English the many little minnows – barely nourishing, and not apt for this new setting.

I’d been working previously on typography and the scoring of sound and movement, with a particular interest in Sign Languages. I knew about early, now-discredited programmes to force Deaf children to speak – rather than using gestural sign-based language, such as that observed by the Abbé de l'Épée in the 18th century – by making them feel the throats of hearing adults. In this particular »lesson« I was very struck by the parallel when Peter, one of the hunters whom I did not know well, frustrated at my inability to reproduce a particular vowel sound, suddenly grabbed my hand and put it on his own throat (an action I change in the poem).

So we have already two languages, but the second, the one to be learned, is only represented by one word – and it is not a regular part of the poem but figures in the title.

See my note below on tikilluarit.

Like an anchor to the ship, which is not on the ship as it is in work. And now the third language – in a first try. The first version is about vowels, trying to keep a natural sounding rhythm, without the »work of the form«.

DIE LEKTION (erster Versuch)

Ich lege meinen Finger um seinen Hals und spüre

wie seine Kehle sich hebt – oder schluckt er die Zunge

hinunter? Er will mir das Wort »Willkommen«

beibringen. Plötzlich erzittert er:

Sein Kehlkopf knurrt, dann ist sein Atem weg.

Er bittet mich, mir diese Vibration zu merken,

und tastet, besorgt wie eine Krankenschwester, nach meinem Puls,

berührt meine Kehle, um ihre Verrenkungen zu spüren.

Werde ich jemals diese sanften Zäpfchen lernen?

Ich bin zu eifrig, ich vergesse es immer wieder,

auf der zweiten Silbe liegt die Betonung.

Mein Echo auf sein Willkommen ist grotesk.

Er lacht, sein Exorzismus für die guillemets,

dunkler Schwarm aus Lauten, die mir nie ins Netz oder über die Zunge gehen.

ALAGASSAQ / THE LESSON

Der Unterricht – oder Die Lektion. The first would be a regularly teaching, practice, exercise – the second a one time lesson: This taught me a lesson. Die Lektion could mean both in German, but I lean to the second.

The poem has already had a series of titles, before this tentative reach for its title in German. First, in draft, »The Hunter teaches me to Speak«; then the Greenlandic word for welcome, »Tikilluarit«, in the first printing of the poem (an artist’s book by Roni Gross with a sound sculpture which echoes the sound of guillemots’ wings). I changed the title once again because it made sense that the word I couldn’t say didn’t appear. What if I gave a reading? Surely it would lack integrity to open a poem by speaking a word, then describe my difficulty with speaking it…

Did the encounter teach me a lesson? Probably, yes.

I place my fingers round his neck and feel

Related to the commentary to »his breath is gone« – place his finger um den Hals oder an den Hals, um has the association of a suffocating grip, an is more tender, as lovers do.

I hoped to generate an undercurrent of violence in the poem – listening and killing are after all the actions of a hunter’s trade. However, an den Hals would be more appropriate here: the »gone« breath in this setting describes the single, subtle out-breath of a word – not the absence of breathing altogether – but the idea of expiration, something of the spirit leaving the body.

Compare Kilime, quoted by Knud Rasmussen: »songs arrive with our breath – in the form of words and music, and not as ordinary speech – and then become the property of the person who understands how to sing to others.« (Lowenstein, 1973.) Or John Berger: »the song settles in the inside of the body it borrows. It finds its place in the body’s guts. In the drum of a drum, in the belly of a violin, in the torso or loins of singer and listener« (Some Notes about Song, Confabulations, p.105).

his gorge rise – or is he swallowing

His gorge rise – as an idiom is translated as »turning his stomach« – the motif is nausea – or should it be translated verbatim: seine Kehle sich hebt.

Verbatim! Thinking about the movements in the throat and how they may be interpreted… with no care for the stomach.

his tongue? He wants to teach me the wordfor “welcome”. Suddenly, he’s trembling:his larynx rumbles, then his breath is gone.

This is the turning point of the poem about teaching to speak, about the hard labor of phonetics – and it is an experience of suffocating, as many of the images have a violent undertow: Gorge rise, fingers around his neck, swallowing the tongue, rumbling of larynx, trembling, contortions (line 8). So to keep both we have to balance the possible associations. This moment is more a LESSON in the second meaning.

Again, not so much actual suffocation (gone) as disappearance (loss) or a transference (Berger’s borrowed body), although the allusion to suffocation is intended. The wider context of the poem is colonialism; on Upernavik I saw the effects of the suppression of the indigenous culture and languages by European settlers over the last 250 years. That the language being taught is now endangered is relevant – the act of passing the language on carries even more weight in such circumstances. There is violence implied here, but also gentle concern and a desire to communicate, on both sides.

The theme of violence runs through Disko Bay: human violence towards the natural world, and also towards other humans. Before travelling to Upernavik I’d been dwelling on the potential violence holds for self-knowledge as well as suffering. My first encounters with this visceral hunting culture, where survival is so often on a knife-edge, turned my preconceptions about cruelty and intimacy on their head. In Arctic legends, like that of Qujaavaarsuk, violence is often transformative – as in Tiresias striking the snakes in the wood. Words are hard work, and they hold the potential for violence too.

He asks me to remember those vibrations,and, anxious as a nurse who takes a pulse,

Nurse: in German we have to settle for a gender.

A male hunter, the ambiguity in English is not intended.

touches my throat to judge its contortions.

Will I ever learn these soft uvulars?

Soft uvulars – second turning point, after his breath is gone. Is it anatomically and only this, or is there a term related to phonemes, too?

This primarily refers to the phonemes, only secondarily to the body. But not so many people are familiar with the term »uvular« it seems… some readers have associated the word with »vulva«. I don’t mind if the meaning is lost, as it echoes other failures of communication within the poem.

Uvular is in German only the phoneme, not the anatomical body part. But the Latin word for it will resonate – much better than Zäpfchen.

I’m so eager, I forget that the stress

always falls on the second syllable.

My echo of his welcome is grotesque.

He laughs, an exorcism of guillemets

In German there are two older words for »Anführungszeichen« – Gänsefüßchen (»little geese feet«, you use them in line 4) and little gulls: Möwchen »«. As this sounds too sweet we could use the French word also in German, but maybe it is better here to be as clear as possible? Anführungszeichen is what people understand.

Yes! I used the French since the English word for the punctuation doesn’t have the association with birds (so the marks/laughter flying away out of his mouth, and the netting of the ending, wouldn’t make so much sense). If that can be conveyed in German, it would be helpful…

dark flocks of sound I’ll never net, or say.

The poem comes back to the frustration of not seeing the word written down… longing for the direction of punctuation, visible on paper, invisible in speech.

Because we have no verb »to net« in German there is the idiom »to go into one’s net«, implying that there is a passive moment in netting. gehen, »to go« would also be used for speaking: »to go over one’s tongue« – »go« not as walking, but as passing.

Net is how the birds are caught in Greenland – the little auks!

I don’t really mind about the specific activity the German verb refers to but it should be something that relates to the hunter’s bird-catching. As opposed to »say« which relates to my own world of work...

How a hunter taught me a vanishing language which is not a written one.

ALAGASSAQ / DIE LEKTION

Ich lege meinen Finger an seinen Hals und spüre

wie seine Kehle sich hebt – oder schluckt er die Zunge

hinunter? Er will mir das Wort »Willkommen«

»Willkommen« has exactly the meaning of an intercultural meeting here: 3 years ago, when the refugees came, everybody was pround of Germany’s »Willkommenskultur«.

beibringen. Plötzlich erzittert er:

Sein Kehlkopf knurrt, dann atmet er aus.

Er bittet mich, mir diese Vibration zu merken,

und tastet, besorgt wie ein Pfleger nach meinem Puls,

berührt meine Kehle, um ihre Verrenkungen zu spüren.

Werde ich diese sanften Uvulare je erlernen?

Ich bin zu eifrig, ich vergesse immer wieder,

dass auf der zweiten Silbe die Betonung liegt.

Grotesk, mein Echo auf sein Willkommen.

Er lacht, sein Exorzismus für Anführungszeichen, ein dunkler Schwarm

aus Lauten, nie werde ich sie im Netz erbeuten oder sagen.

Wie ein Jäger mir seine aussterbende Sprache beibrachte, die schriftlich nicht fixiert ist.

OQQERSUUT / THE MESSAGE

Since I can’t post a letter this far north,

I’m sending you an Arctic snowstorm,

the worst weather London’s ever known:

deep drifts resisting shovel, salt and thaw.

Since I can’t touch your winter skin

I appoint the most delicate snowflakes

to fall into your arms, kiss your cold face

and silence the city I loved you in.

I can’t judge your heart’s temperature,

although I lay out the last glacier

over the miles between us. Don’t you hear

the wind? It calls to know your nature.

It’s warmer than you think, for I have dressed

that wild inquisitor in my own breath.

DIE BOTSCHAFT (erster Versuch)

Da ich keinen Brief dir aus dem hohen Norden senden kann,

schicke ich dir einen Schneesturm, arktisch,

das schlimmste Wetter, das London je gesehen:

tiefe Verwehungen, die Salz, Schaufel, Tauwetter widerstehen.

Da ich an deine Winterhaut nicht reichen kann,

schicke ich dir feinste Flocken, die als Schnee

in deine Arme fallen, dein Gesicht kühl küssen

und die Stadt in Stille hüllen, in der ich dich geliebt.

In this version it is city as well as the silence, in which »I loved you in«. I lose a bit of the sound if I make it clearer: »und in Stille die Stadt hüllen in der ich dich geliebt«.

Silence has in German two meanings. Stille – which applies to things – and Schweigen – if you do not talk. In a poetic text of course I can substitute one for the other: »und in Schweigen die Stadt kleiden, in der ich dich geliebt«.

I was thinking primarily of things – the traffic coming to a halt, the muffling of other urban noises in snow – but as the city is almost personified, indeed it could be seen as Schweigen, the city’s voice muted. It is maybe best to keep the assonance with the beautiful kühl küssen? but it feels like the translation could go either way, here.

Deine Herzenstemperatur kann ich nicht ermessen,

aber über all die Meilen zwischen dir und mir

breite ich die letzten Gletscher. Hörst du nicht

den Wind? Er ruft, will deinen Zustand wissen.

Nature is the real nut. Here, is it more the general situation of the beloved?

What is nut? »nature« refers back to »heart’s temperature« – the nature of the affections – and really just reiterates that before the final couplet. But it could, and does, refer to character in general (and the pun on »natural world« in English sums the conceit of the poem up, of course). ruft has a wonderful sound here, it really captures the buffeting voice of the wind.

Nature as a difficult problem to solve: that’s all I wanted to say with »nut« – Zustand

Er ist wärmer, als du denkst, denn ich hüllte

in meinen eigenen Atem den wilden Befrager.

Or: »den wilden Inquisitor in meinen eigenen Atem ein«.

Inquisitor – in German it is a real Fremdwort, but it is known – Befrager would be neutral.

It sounds like both have advantages – I wonder, though, about the effect of placing something attention-grabbing (i.e. a foreign word) in the last line, in this relatively soft and unshowy (though snowy) poem? But then the wind is coming from outside… over to you!

This time the sonnet is obvious, I have assonances for rhymes and I often use words which allude to the tradition of metered poetry: »ermessen« instead of »messen« to have an extra syllable, alliteration »kühl küssen«, in verse 4 you have a line of words with 1, 2, 3, 4 syllables – which adds to a folksy Shakespearian music, without using old-fashioned words.

Wonderful to have those assonances. As you see, the English is mostly only half rhyme, but better to keep the meaning and flow than force the form. The poem came into its own when I broke up the quatrains with white space: it’s a sonnet, but disguised in snowdrifts.

This time the sonnet is obvious, I have assonances for rhymes and I often use words which allude to the tradition of metered poetry: »ermessen« instead of »messen« to have an extra syllable, alliteration »kühl küssen«, in verse 4 you have a line of words with 1, 2, 3, 4 syllables – which adds to a folksy Shakespearian music, without using old-fashioned words.

OQQERSUUT / DIE BOTSCHAFT

Da ich keinen Brief dir aus den hohen Norden senden kann,

schicke ich dir einen Schneesturm, arktisch,

das schlimmste Wetter, das London je gesehen:

tiefe Verwehungen, die Salz, Schaufel, Tauwetter widerstehen.

Da ich an deine Winterhaut nicht reichen kann,

schicke ich dir feinste Flocken, die als Schnee

in deine Arme fallen, dein Gesicht kühl küssen

und die Stadt, in der ich dich geliebt, in Stille hüllen.

Deine Herzenstemperatur kann ich nicht ermessen,

aber über all die Meilen zwischen dir und mir

breite ich die letzten Gletscher aus. Hörst du nicht

den Wind? Er ruft, er will deinen Zustand wissen.

Er ist wärmer, als du denkst, denn ich hüllte

den wilden Befrager in meinem Atem ein.

Das Gedicht kam zu sich selbst, als ich die Quartette mit weißen Raum unterbrach: es ist ein als Schneewehen verkleidetes Sonett.

LESEN

Über Natur schreiben, das heißt immer auch über unser Verhältnis zu ihr schreiben. Ein Verhältnis, das sich in den Begriffen zeigt, die wir für sie finden. In Cormac McCarthys Roman Die Straße sind die Worte noch da (Gras, Amsel), aber ihr Bezug ist verloren gegangen, ausgelöscht, auf der anderen Seite der Apokalypse zurückgeblieben. Robert Macfarlane greift diese Bewegung auf: Er konserviert die Wörter, behält sie in Erinnerung, um so zumindest das Verschwinden der Phänomene, die sie beschreiben, anzeigen zu können. Denn die Phänomene verschwinden spätestens dann, wenn wir keinen Begriff mehr für sie, von ihnen haben. Im Gespräch mit Hans Jürgen Balmes im Literaturhaus München geht er dieser Bewegung nach. Ein Auszug aus einem Gespräch, das die Verbindung von Lesen, Schreiben und Übersetzen aufführt.

Robert Macfarlane wird 1976 in Nottinghamshire geboren. In seinen Büchern nimmt er Landschaften und die Natur in den Blick und schreibt über unser Verhältnis zu ihr. Er ist Fellow der Royal Society of Literature und Gründungsmitglied der Naturschutzorganisation Action for Conservation. Auf Twitter postet er jeden Tag ein Wort, das Natur- und Landschaftsphänomene beschreibt. Für sein neues Buch Im Unterland, 2019 bei Penguin Random Hause erschienen, hat er in den dunklen Landschaften unter der Erdoberfläche recherchiert und sicher unter anderem in die Pariser Katakomben und einen Atomendlagerstollen begeben.

Hans Jürgen Balmes wird 1958 in Koblenz geboren. Er ist als Übersetzer, Lektor, Herausgeber und Autor tätig. Nach einem literaturwissenschaftlichen Studium gibt er einen Novalis-Kommentarband und die Gesammelten Werke von Hölderlin heraus und wird Lektor im Carl Hanser Verlag, dann im Ammann-Verlag und leitet schließlich das Lektorat für internationale Literatur im S. Fischer Verlag. Zu den englischsprachigen Autor:innen, vor allem Lyriker:innen, die er übersetzt, zählen W. S. Merwin, Robert Hass, Martine Bellen, Barry Lopez, Ed Hirsch, Nancy Campbell und John Berger, mit dem ihn eine enge Freundschaft verband. Er schreibt an einer Naturgeschichte des Rheins, für die er auf, am und neben dem Fluss gewandert ist. Hans Jürgen Balmes lebt bei Frankfurt am Main.

Wir danken dem Literaturhaus München für die Aufzeichnung des Gesprächs zwischen Robert Macfarlane und Hans Jürgen Balmes. Die Gedichte von Nancy Campbell entstammen ihrem Debütband, Disko Bay, 2015 erschienen bei Enitharmon Editions. Die Übersetzungen der beiden ersten Gedichte von Nancy Campbell werden auf deutsch in den manuskripten erscheinen, die drei letzten sind in der Neuen Rundschau, Heft 1, 2020 mit dem Themenschwerpunkt »Nach der Natur« enthalten. Das Gedicht von Lal Dêd stammt aus I, Lalla. The Poems of Lal Dêd. Translated from the Kashmiri with an Introduction and Notes by Ranjit Hoskote, 2011 erschienen bei Penguin Random House India.

Produktion: Max Farr, Konstantin Schönfelder, Holm-Uwe Burgemann

Fotografien: Field Notes © PRÄ|POSITION 2020; Nancy Campbell, »Nancy in the Snow« © Fondation Jan Michalski 2017 von Tonatiuh Ambrosetti, »Nancy Campbell« © Nancy Campbell von Annie Schlechter (2018), »Hans Jürgen Balmes« © Hans Jürgen Balmes, »Robert Macfarlane« © Bryan Appleyard

Hat Ihnen dieser Text gefallen? Dann werden Sie Freund:in von PRÄ|POSITION und helfen Sie mit Ihrer Mitgliedschaft über Steady, dass auch kommende Texte lesbar bleiben.